Needles can also serve the function of languages. In traditional Chinese, “ 针 ”, the Chinese character of “needle”, has the same pronunciation as “ 箴 ”, which means “admonition”. Therefore, in Chinese, the word “needle” shares the meaning of admonition without implication of gender. The long bamboo needle for weaving and knitting, and the crewel needle for embroidery, all share the metaphor of admonition. Both in Chinese and western cultures, the fine needle is connected to languages. It represents the sensation of human body, the activation and revival of humanity, the cultivation and self-reflection of the soul, and a prophesy of the future. The reason is that needle is regarded as the origin of writing languages for its similar appearance of a pen. Therefore, the origin of the admonition metaphor of needle is embedded in its fundamental approaches--weaving, embroidering, and a series of art works, which are all relevant to needles, in this way traditional weaving and knitting echo to the reality and are revitalized.

The concepts of weaving and human body are intertwined; textiles of different materials, including wool, hemp, silk, and cotton, give us unique and special body sensations. Weaving is not only a body protection but also serves as a symbol of identity. Our physical body not only indicates temperature, feelings and identity, but also stands for memory and history. Skin is a protection to our body and clothes are regarded as the “second skin”. Today, in a multicultural era, textiles have another function-a symbol of identity of different races and regions, showing the distinction of different times and groups; textiles are one of the most familiar things in our daily life, however, their identity is changing and disappearing gradually. This is how textiles echo to the history and bodily memories.

Weaving could be seen as two-dimensional fabric making and as an approach of three-dimensional shaping. As a different type of shaping a figure, weaving displays the techniques and the experimental characteristics of modern fiber art. It has inspired a series of conceptual transformations and becomes related with social reality. The meaning of weaving not only represents the behavior of weaving or creating a certain shape, but also contains the concepts of “constructing” “building” and “perspective” and involves many social factors like war, stock market, economy, biology, science and technology, ecology, commodity and policy. Shaping is how weaving echoes to forms and concepts.

The manufacturing process of weaving is a vivid and important social scene. Weaving originated from households, developed in workshops, transformed in local places, and was activated in factories. Weaving raises many questions for people to think about and drives us to find answers in our social reality. There is plenty of information of the local and people in the scene: weaving is not only presented on the individual workers, but also based on industry, enterprises and groups. It develops in the specific daily scenes and reflects numerous social realities. In order to react to the social problems, weaving becomes an intermediary of thinking, and continuously raises questions. This is how weaving responses to social scenes.

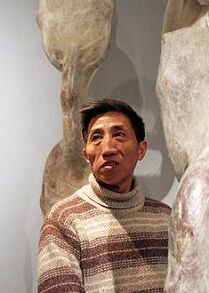

Liang Shaoji's Solo Exhibition: Cloud above Cloud