Ireland/Canada

Linen fibre, derived from the flax plant, was an economic commodity introduced to Northern Ireland as part of its settlement and colonization. Everybody in Northern Ireland, from my generation or earlier, was familiar with the sickly-sweet smell of flax “retting” - that is the process of soaking the plant stalks to decay off the outer fleshy matter and leave the remaining core fibrous material - in stagnant 'dams' which were dotted over the landscape in rivers and streams, besides fields in the previous century. One could say that, during The Troubles, the smell of burning bodies, tragically, became almost as familiar a stench.

In my own life (b. 1967), The Troubles endless news coverage and personal anxieties, grieving and fears migrated to Canada (1970) with me and my family.

Linen and lace became a part of the fabric of Northern Ireland society, on both sides of the Irish/Ulster-Scots religious-ethnic-political divide. Flax and linen, and the mills that produced the finished linen products, are iconic to the Northern Ireland way of life. While domestic linens are rarely in use any more because of the care and ironing that these natural fibers demand-- and, of course, linen's replacement by cheaper cotton and artificial fibres -- , Northern Ireland’s individuals and communities remember life-with-linen seemingly always in the background. In the same way, the Names of those who have died in The Troubles are always with the living generations of contemporary Northern Irish citizens.

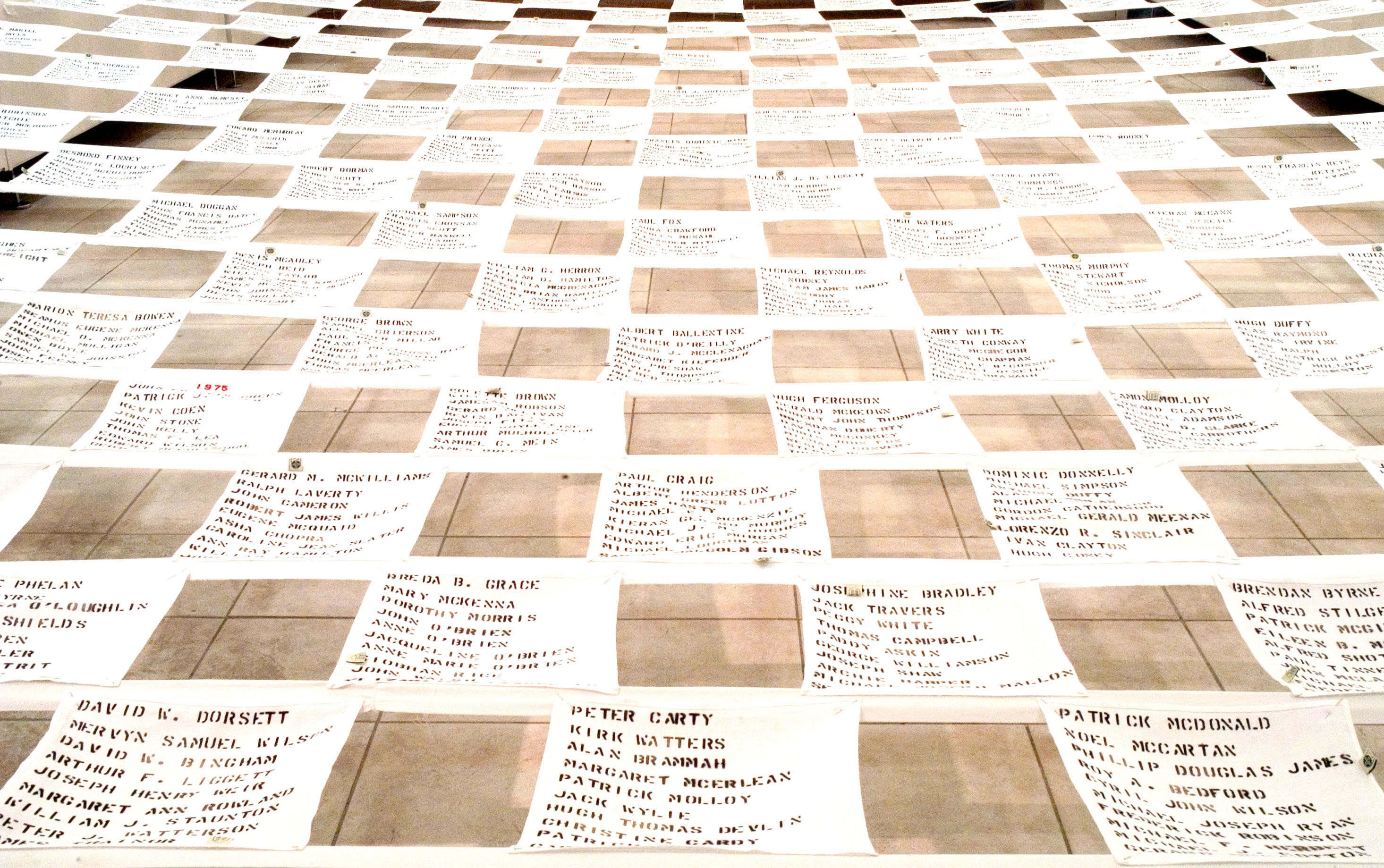

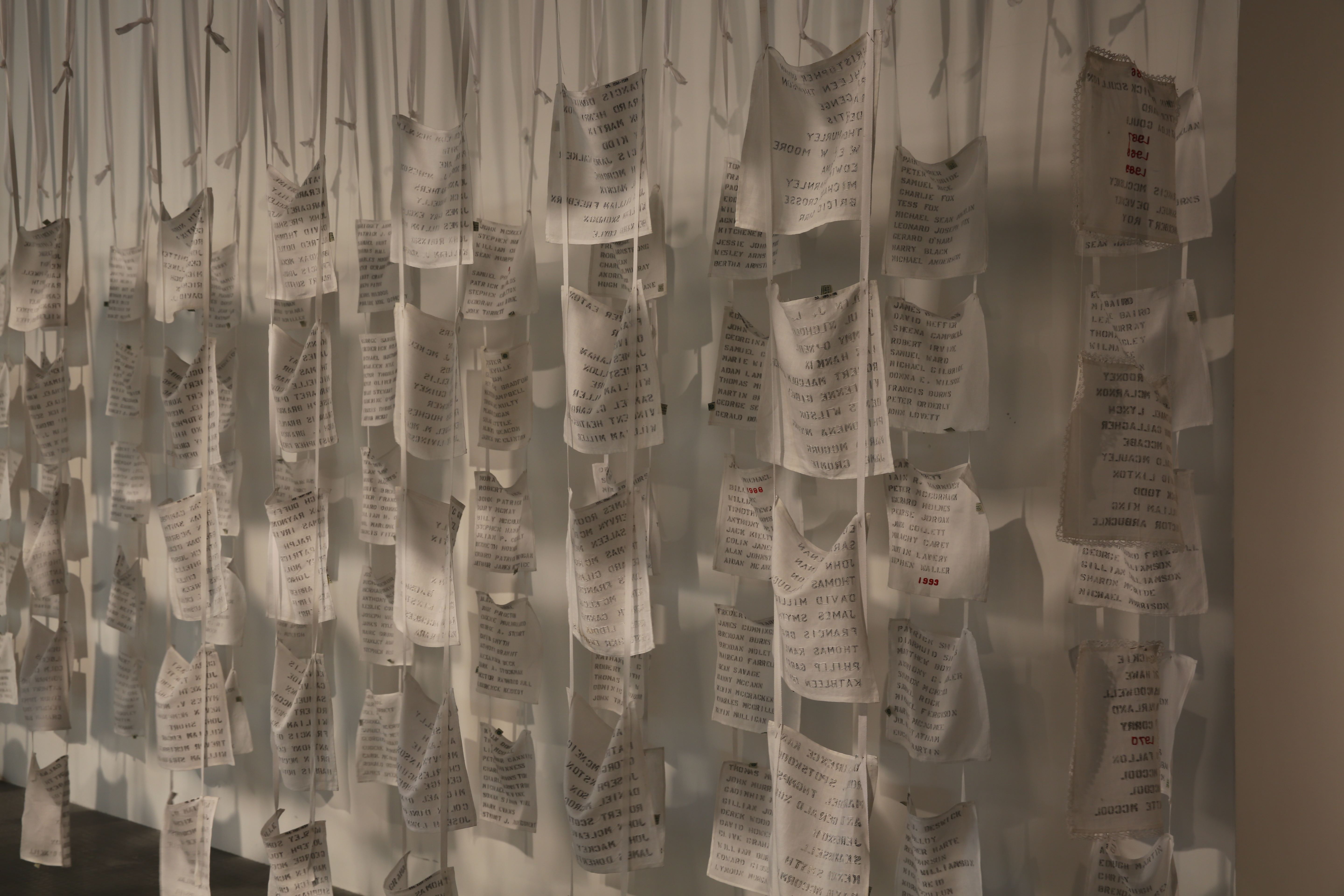

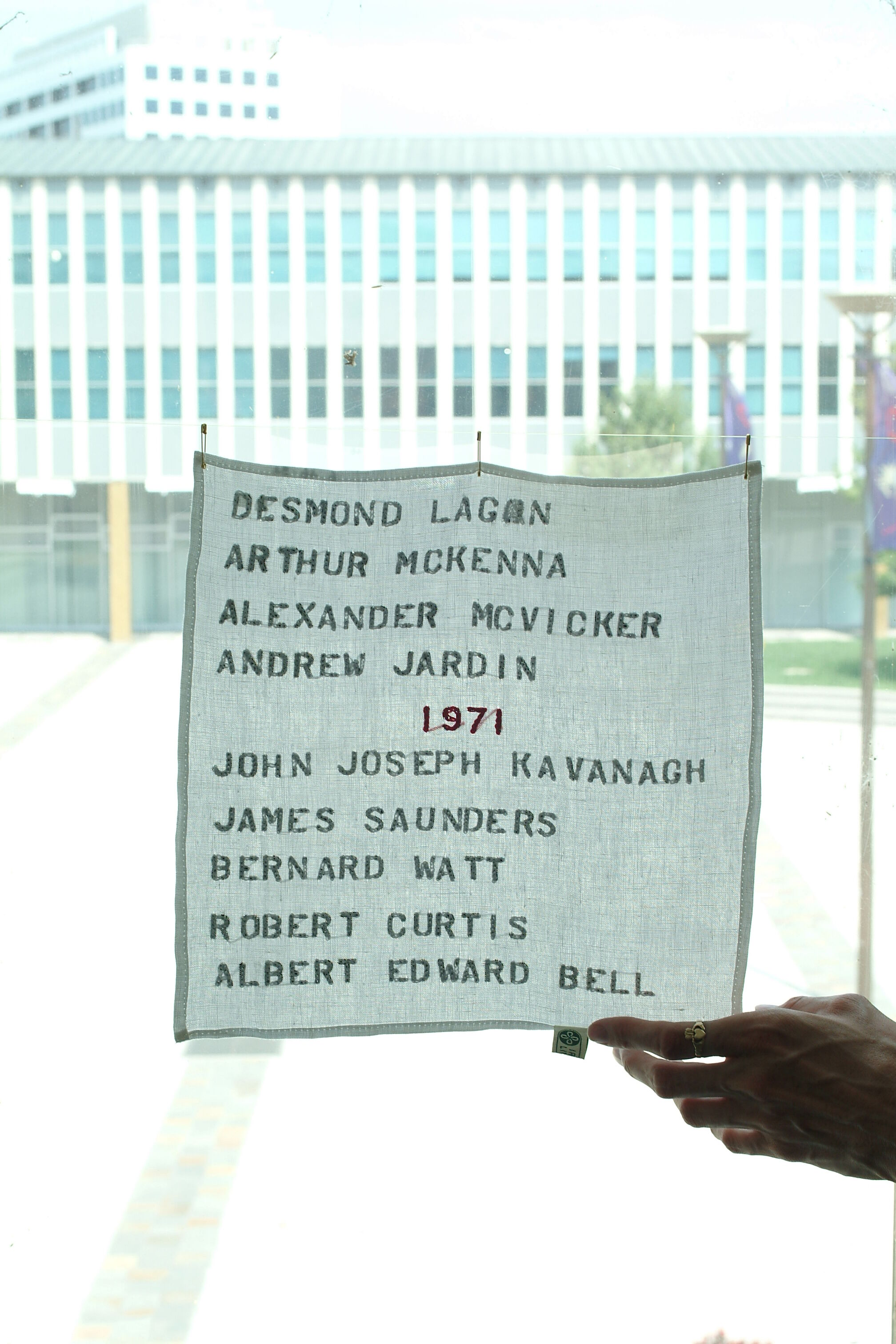

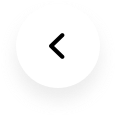

It was because the part played by linen was pivotal in the socio-economic development of my hometown, and Ulster as a whole, that I chose to use the humble linen handkerchief as a frame for the names of the almost 4000 people who died in The Troubles conflict in the years 1966 - 2006. The Names List on this memorial is embroidered by hand in chain stitch.

My mother, like so many others, ironed, darned, and did utilitarian sewing daily. During times of chaotic warfare, it can be said that daily, domestic chores enable ‘routine’ of ‘normal’ life to ‘go on’ like the World War II slogan, “make-do-and-mend.” My paternal grandmother used her creativity to do more than darn sheets for ‘home economic’ reasons; she was skilled at white linen “drawnwork,” such as on the edges of family heirloom pillow cases and to decorate my girlhood dresses. Drawnwork, according to USA feminist folklorist Linda Pershing, is symbolic of the erasure of women’s leadership, such as in worldwide peace and ecological movements [REF].

Finally, internationally, the waving of the handkerchief is a universal sign for goodbyes and for catching our tears of both grief and reconciliation. Even today, you can buy a package of handkerchiefs in airport shops worldwide. For immigrants and ‘survivors’ of tragic circumstances, such an item is more than just a sentimental gift.

My question is can my Linen Memorial, as a socially-engaged community-based public artwork, help and contribute to Truth, Forgiveness, Healing-through-Remembering and / or Reconciliation in Northern Ireland?

Only time will tell…