Curated by Grant Watson

Supported by INIVA

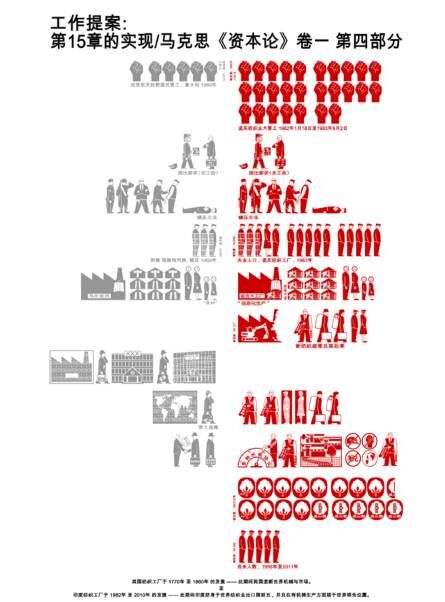

Lightweight but valuable cloth is a commodity which for centuries has generated contact between cultures — through the exchange of goods, as well as the transfer of knowledge (willingly or otherwise) in terms of design, colour, motif, and the technologies involved in production. The production and trade in textiles was linked to European colonisation, and can be understood in terms of a power imbalance which saw the extraction of raw materials from the colonies, along with the use of slavery, protectionism at home, and dumping abroad of goods. Karl Marx writing about the cotton trade in Capital, as well as in a series of articles published in the New York Herald Tribune, noted the impact of British policies in India as well as the expansion and contraction of the industry in terms of the effect it had on workers, who were periodically ‘attracted’ then ‘repelled’ from the factory system. In the post colonial period, these imbalances were maintained through treaties that favoured the rich world, such as the Multi Fibre Agreement (1974–2004) which severely limited the import of textiles into Europe from the developing world, as well as the setting up of Special Economic Zones (SEZ) where employees worked without basic protections. But at the same time textile production has been linked to forms of resistance, from the collective of seamstresses in Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What is to be Done (1863) to the eighteen month strike by Mumbai’s mill workers from 1982–83, probably the largest and longest strike in history.

Developing on these ideas, the touring exhibition Social Fabric has been specially reconfigured for this Triennial of Fiber Art. Through a range of media including installation, photography, drawing, film, textiles, audio recordings, books and historical documents, the exhibition looks at textiles and its relation to capital, labour, colonisation, international trade, and radical politics with a particular focus on India.

Notes on the Mill Lands of Mumbai

The Resistance

Much of the discussions around the mill lands of Mumbai have been about the resistance put up by the mill workers and the activists. The resistance was in the context of industrial restructuring in Mumbai.

The textile mills of Mumbai had started closing down in the mid-1980s. There were several reasons for this – the overall city economy was changing, with formal industry in the middle of the city discouraged and systematically dismantled. Moreover the textile mills of Mumbai were left with obsolete technology without investment, making their production incapable of competing with other production centers. On the other hand, the labor unions had become militant with their demands for higher wages. The mill owners also looked at this as an opportunity to redevelop the mills into commercial property as real-estate prices in Mumbai were skyrocketing. By the mid-2000s, the mills of Mumbai were almost completely wiped out. Many of them were pulled down. The lands on which they stood were hurriedly developed into highly priced real-estate.

The workers responded to this context with a series of resistance movements, which began with a strike in the mid-1980s, one of the largest and longest strikes in history, demanding better wages. But when the context of industrial restructuring was understood, the resistance transformed into an effort to restart the textile mills. When this effort failed, the resistance changed into a claim for outstanding dues. Currently, after the mills have been razed and new real estate built in their place, the resistance has mutated once again into a bargain to get at least a small share from the profits of redeveloping mill lands – the demand is now for a small piece of property – articulated as a house for each worker.

With large industries shutting down, the nature of work in the city also changed – some of the mill workers who lost their jobs took up work – as watchmen, liftmen, hawkers, estate agents – but most of them did not end up doing anything. They found themselves misfits in the new economy. For most the menial work they got in place of these jobs was not dignified enough. The burden of running the family mostly fell to the women, who undertook several entrepreneurial activities from within their homes – they would run tuition classes, catering services, etc.

The Lament

Lament and nostalgia has been central to the discussions of the mill lands largely mobilized by architects, planners, historians and other urban intellectuals who saw the mill land transformation as a lost opportunity. They had proposed to relieve the stresses of the city by creating cultural infrastructure and amenities in the place of closed mills.

By the beginning of the 1990’s there was already a consensus on the lack of future for the cotton textile mills in the city. Cognizant of this, the government drafted a regulation for allowing redevelopment of the mill lands. This was the famous ‘Regulation 58’ in the Development Control Regulations of Mumbai, 1991 enacted under the Maharashtra Region and Town Planning Act. According to the regulation, ‘Open lands and lands after demolition of existing structures inside a mill could be redeveloped such that it is divided into three parts – one for commercial development, one for housing and one for amenities’. This ensured that the gains from the redevelopment were shared by the owners (who were allowed to develop real-estate), laborers (who were to get all their dues and a house in a high priced locality), and the city (which was to get additional amenities). Several mill premises underwent immediate redevelopment. A number of high-rise buildings came up, pressuring the already burdened municipal infrastructure. Under pressure from the architectural and planning community, the government appointed an expert committee under the chairmanship of a renowned architect Charles Correa to prepare an integrated plan for redevelopment of the area. When the research began, a cartographic map was prepared of the existing landscape, which showed the lack of open spaces in the area. The consequent agenda of the research group was to use the opportunity of available mill lands to provide the area with public space. The final proposal identified buildings that could be conserved for public use and proposed a new, integrated open space structure for the city. The classical notion of open public spaces dominated the proposal and the cartographic physical plan informed it. Case studies from European and American industrial land redevelopment were frequently used to argue the case. The undercurrent of the land economics and politics of development were however never understood. While the workers were unable to relate to the concern of creating public space, the owners saw the proposal essentially grabbing their land for ‘public use’. The proposal failed to gather support from any of the concerned actors and the government shelved the plan.

Meanwhile, the mill owners conspired with the government and changed the regulations whereby they could get almost the entire property to redevelop into real estate. This change was done surreptitiously – it was announced in one of the least read newspapers and was termed as a minor modification (which does not attract much discussion) where the words, 'and lands after demolition of existing structures' were struck off. The new rule stated, ‘Open Lands inside the mill could be divided into three parts– one for commercial development, one for housing and one for amenities’. And there was very little open land inside the mills. The lands under the existing structures were allowed to be developed by the owner as real-estate. As a result the land to be given to the city substantially reduced and most land was to be redeveloped into real-estate. Many environment and heritage activists filed a petition in the judicial court against the changed regulation. While the courts decided to uphold the changed rule, they also directed that buildings that have ‘heritage value’ should not be demolished. An exercise was undertaken to identify buildings with ‘heritage value’. Most chimneys were listed and the government agreed to retain them. Today these chimneys sit clumsily in the midst of towering apartment and office buildings. An industrial museum is also proposed in one of the mills.

The fervor of development put immense pressure on the chawls of the area to undergo change. A chawl is a building between one and four stories, with small tenements strung along a corridor, with shared toilets. This was the urban housing type for the working class in Mumbai. By the beginning of 2000, several old dilapidated chawls started getting redeveloped. The government had passed a regulation decreeing that if tenants of an old chawl wanted to redevelop, then additional floor space could be built which could be sold in the open market to compensate for the redevelopment cost. However, the tenants were generally unable to mobilize resources for such a redevelopment and depended on developers. Today, most chawls are extremely contested spaces with the developers and tenants in constant conflict over the speculative profits of real estate.

The Celebration

There has been a considerable amount of celebration of the transformations taking place in the mill lands – celebration of changing landscapes, of the new economy, of new spaces and new people. While the agents connected with real estate like the mill owners, construction industry, financiers, etc. found opportunities in the shutting of the mills; several others also welcomed the change – many intellectuals saw this as a birth of the new liberalized and globalised economy which had to be taken advantage of; many environmentalists saw this as an opportunity to relieve the city from industrial pollution; many practitioners of the culture industry found the cadaver of the old mills interesting to house art galleries and other cultural spaces; and many new professionals from the commercial and financial sectors found work spaces and houses in the newly redeveloped mill lands.

The lands occupied by the mills changed quickly. In some cases new activities started taking place within the old mill buildings – the warehouses became malls, restaurants and art galleries, the spinning and weaving sheds became banks and other commercial offices and shops and other industrial infrastructure like the boiler room or the carpenter’s workshop became pubs and cafes. In other cases however, the old mill buildings were completely pulled down. The debris was used to fill up large water tanks inside the mills that were earlier used for fire protection and humidity control in the spinning sections. In place of warehouses and sheds, up came malls, call centers, art-galleries, media centers and commercial offices in odd shapes and forms.

Earlier, the new buildings and activities seemed to sit awkwardly in the landscape of mills and mill workers. Many of the new malls, pubs and shopping places were protected by armed guards, security cameras and metal detectors. However, over time the spaces within and outside the mills changed. Absurd combinations of enterprises have come up in the vicinity – interior designers combined with stock-brokering agents, travel agents with courier and security services, money transferring agencies with an employment bureau or a contract labour agency, etc. Over time the familiarity and the comfort level has increased and today hoards of people visit the malls inside the old mills every day. The malls promise ‘a million experiences’. These have become performative sites where people live their aspirations by just floating around in these new spaces, sites of borrowed pleasures for those who cannot afford the goods on sale.

For some time now, the discussions around the textile mill lands of Mumbai have been polarized between the ideas of resistance, lament and celebration. Life, on the other hand, works out in a multiplicity of ways.

Global Fabric Bazaar

Ka-Kin Cheuk

Keqiao in Zhejiang Province of eastern China is the world’s centre for wholesale fabrics (mianliao). ‘Fabrics’ refers to industrially processed, semifinished, light textiles (qingfang) that are woven, flocked, knitted, dyed, and printed before trading. These fabrics are further processed outside of China, eventually becoming garments, home textiles, or other consumer products in the downstream of the textile industry. This area is the home to twelve mega-size marketplace buildings, in which about 22,000 outlets wholesale more than 10,000 types of fabric. More than 80 per cent of the fabric sector is small- and medium-sized enterprises, and about 200,000 Chinese, which is nearly half of the local population, work in the fabric industries. These people have profoundly contributed to both the county’s and the nation’s economy, with local fabric industries generating more than 60 per cent of the county’s gross domestic products (GDP), and Keqiao distributed over 212 hundred million units of fabrics, which was one-third of all fabrics produced in China in 2009.

Given the varieties of product and, more importantly, their bargain prices, these fabrics have been exported in bulk from Keqiao to countries all over the globe. In fact, Keqiao has become a household name in the global textile markets, particularly the low-end ones in South Asia, Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa. Indians, especially Sindhis, who have maintained extensive business connections in these regions and have traded fabrics for decades, have emerged as a major group of trading agents in Keqiao. Around 10,000 such Indians, either self-employed or employed by others, are now based in this small place of China, finding it necessary to live there in order to operate their businesses. These Indians are operating in Keqiao what can be described as an intermediary economy because their primary role is to broker fabric export deals between overseas buyers and local Chinese suppliers. In the process, they earn commissions from either one or both sides. The global fabric trade is a multinational process that entails several rounds of trading and industrial processing, and the intermediary businesses found in Keqiao constitute only a small part of the process; nonetheless, it is an indispensable part.

Throughout my anthropological field research in Keqiao (2010-2012, 2016-2017), I have taken a close and detailed look—to the extent possible—at everyday encounters in Keqiao among various types of intermediary business players, especially the Indians and Chinese who leverage encounters to create a local market niche. My research is set out to explore how the local encounters among these players form a workable intermediary economy with its own internal logic, and to what extent it can function, notwithstanding the unavoidable and unpredictable disturbances from the global economy at large.Indian traders in Keqiao, who are situated in the middle of a larger trading process, play their part in completing the circuit of global fabric trading. As such, no one in Keqiao’s fabric market can escape global market fluctuations, regardless of how much they have achieved in the local fabric market.

However, simply treating the Indian traders like a cog in the global trading wheel risks overlooking what they are actually doing in Keqiao. It might be easy to tag all of them as ‘brokers,’ ‘trading diaspora,’ or ‘connectors’ without going any further or deeper, as if they can be neatly defined as some special group advancing economic globalization. It should be noted that these Indians are running an intermediary economy not because they want to bridge the gap of globalization or because they want to establish a collective ethnic economy. Rather, this intermediary economy represents the sum of their individual calculations and case-by-case business decisions. Such decisions, in and of themselves may be logical, but they can create ‘frictions’ (Tsing 2005) in other parts of the trading process, especially between the global and local, as well as between the powerful and less powerful.

That is to say, intermediary players, in order to survive in the market, always need to prioritize their own interests, not necessarily those of their local and global clientele. It can be reflected in some double-sided actions of intermediary operations I observed in Keqiao, such as disclosing product information while keeping secret certain parts of it; simultaneously creating trouble for their clientele while helping them resolve these troubles; and facilitating connections between buyers and manufacturing factories while making sure that the two parties do not trust each other. In short, intermediary players do as much to connect as to block, ensuring that export deals proceed smoothly. Indeed, what Indian traders must learn to do quickly in Keqiao is to prove the value of their intermediary businesses, which counteracts the current trend of dis-intermediating in global capitalism.

As I conceptualize them, the stories of Indian traders can be analysed through the (1) local lens of fabric materiality and (2) the self-making of a bazaar economy, with the combined result leading to an alternative mode of global economy. Considering these all together, I suggest that the dynamics can be understood as a global fabric bazaar.

Fabric materiality is rather unique when compared with that of other industrial commodities because its industrial production is a highly resilient process in which the fabrics’ physical composition—namely its raw materials, colours, patterns, density, elasticity, softness, weight, processing speed, interweaving methods, stitching techniques, and a wide range of minor qualities—can all be adjusted or modified to meet buyers’ requirements or budgets. Unlike other standardized commodities, fabric trading is extremely adaptable to rapid market changes or, more precisely, the rapidly changing fashion, taste, preferences and, above all, budget of buyers. Thus, business negotiations usually entail painstaking rounds of phone and in-person office calls, tireless arguing, double-checking of numbers, and forceful bargaining and compromise between the sellers and buyer of fabric. All of these intensive interactions give each party a say on what is to be traded, which is subject to change throughout the deal-making process.

The notion of fabric materiality can be precisely summarized by a popular Chinese saying: jianghuo jiujia. This literally translates as ‘making the goods according to how much one can pay for it.’ Capitalizing on such versatile and flexible fabric materiality, tens of thousands of Chinese fabric suppliers make their living in Keqiao. Such local fabric sectors can be called a ‘bazaar economy,’ in which ‘information [of the trade items] is poor, scarce, maldistributed, inefficiently communicated, and intensely valued’ (Geertz 1978: 29) among these suppliers. In such a disorderly market setting, to find a reliable supplier and to get the best value of purchase—at least in the way that the buying side would view it—requires a high level of commitment, engagement, and persistence from the individuals who are direct participants in the deal-making process. In Keqiao, this individual can, of course, be a buyer, but more likely is an intermediary player, such as an agent and subagent working for a trading company. During the deal-making process, this individual needs to search extensively for local suppliers; and once a particular supplier is chosen, to bargain intensively for the best deal (Geertz 1979: 224). This is tedious and exhausting work, which nonetheless gives the individual great leeway to build up his or her own agency in the fabric trade. This is particularly true for some Indian subagents I met in Keqiao. When working on these two tasks—researching and bargaining—for their companies, the subagents were, at the same time, trying to acquaint with as many local Chinese suppliers as possible, often without the knowledge of their bosses. They believed that such a contact list would become vital to realizing their own entrepreneurial dream in Keqiao. In other words, many subagents worked extremely hard not so much for their bosses’ companies but because they wanted to launch their own businesses in the not-too-distant future. Considering this scenario in a bazaar economy, it is not possible to prevent subagents from eventually starting their own businesses.

In light of the foregoing, the bazaar economy model is important not because it is ‘the precursor or prototype of the modern capitalist competitive market’ (Favero 2010: 62), which can still be found in many parts of the capitalistic world today (e.g. Bestor 2004), nor because bazaars are convergent spaces for economic exchange, political discourses, social relations, and cultural representations (e.g. Bayly 1983). It is important because the bazaar economy model, as in the example of Keqiao, offers realistic hope to individual players who look forward to becoming self-enterprising, and this is especially true for those who start from nothing. Even though these individual players may start as inexperienced, with a lack of capital or with the possibility of being exploited, they can gain experience, build networks, and accumulate capital, all of which can be transformed into tools to craft their own future businesses. Given that the fabric trading economy in Keqiao operates in ‘an enormously complicated, poorly articulated, and extremely noisy communication network’ (Geertz 1979: 125), every individual player, if directly engaged with local markets, has a rather fair chance to tap into ‘the ambiguity, scarcity, and maldistribution of knowledge generated’ (323) by the fabric trading economy. In this vein, an examination of individual players’ self-making strategies in the fabric bazaar economy should reveal them as more than simple constituents of a given bazaar economy.

References:

Bestor, Theodore. 2004. Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bayly, Christopher. 1983. Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1780-1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Favero, Paolo. 2010. “Bazaar.” In Ray Hutchison, ed., Encyclopedia of Urban Studies, 61 - 65. London: SAGE.

Geertz, Clifford. 1978. “The Bazaar Economy: Information and Search in Peasant Marketing.” The American Economic Review 68(2): 28 - 32.

---. 1979. “Suq: the Bazaar Economy of Sefrou.” In Clifford Geertz, Hildred Geertz and Lawrence Rosen, eds., Meaning and Order in Moroccan Society, 123 - 314. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsing, Anna. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.