Michał Jachuła

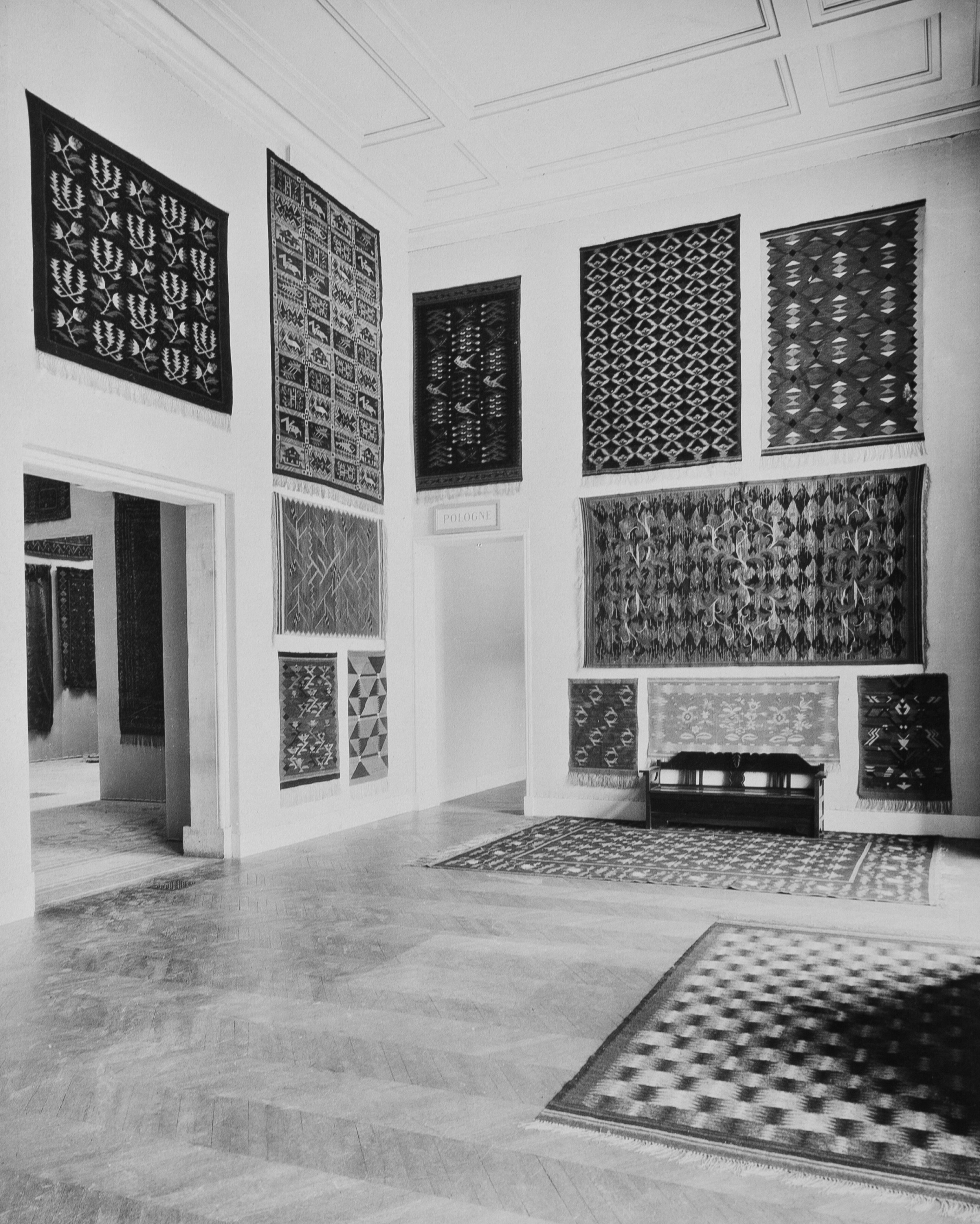

The exhibition of Polish art at the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts in Paris in 1925 was the first foreign presentation of works by Polish artists from Poland after the country regained independence (in 1918). With a strong focus on textile art, the exhibition consolidated the position of the national style which later became to be known as the Polish Art Deco. The style was promoted in disciplines of art including those based on solid craftsmanship, such as textiles and furniture. The new art of the independent country was where two traditions and generations met: Warsztaty Krakowskie (the Cracow Workshop), a co-operative association modeled on the Vienna Workshop, established in Cracow in 1913, and the programme of Wojciech Jastrz?bowski’s Workshop of Solids and Planes at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, reinitiated in 1923. The Workshop, which trained first-year students, taught that the form derives directly from the nature of the material and the tools applied. In the inter-war period, despite its strong links to folk art and references to ancient Polish woven works, fibre art followed the modern Classicist style. The quest for a new vocabulary of textiles, an interest in the tradition of folk art, and a specific approach to materials will in subsequent decades help to develop the Polish school of textile art.

During WWII (1939-1945), Poland suffered the biggest losses world-wide, including a major loss of cultural goods. The priority was to rebuild the country; no wonder that the development of art stalled for several years. The after-war period was a time of poverty and dealing with the war trauma. Poland’s political system was subservient to the USSR. The doctrine of Social Realism, imposed in 1949-1953, demanded that works of art have a realistic form and a socialist message. The political “thaw” and the transition after 1956, when artists regained creative freedom, marked the end of Social Realism.

The late 1950s and the role of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts proved key to fibre art in Poland. Fibre art classes were given at the Warsaw Academy by three prominent professors, pre-war graduates of the Academy: Eleonora Plutyńska, Anna ?ledziewska, and Mieczys?aw Szymański. Notwithstanding all differences in the professors’ curricula, individual interests and teaching methods, the common denominator of their approach was respect for historical Polish traditions. All encouraged students to experiment and take on ambitious challenges while exploring the tradition of folk art. The high quality of education in this discipline of the arts and an emphasis on new languages of fibre art sought by students resulted in spectacular creations.

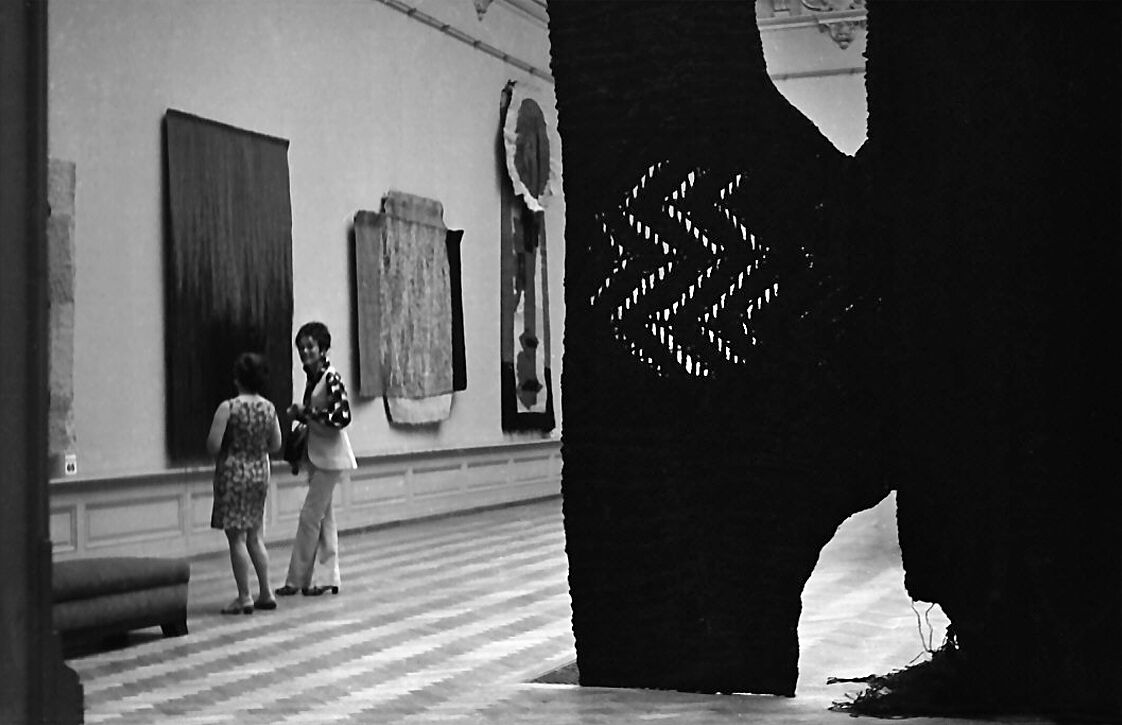

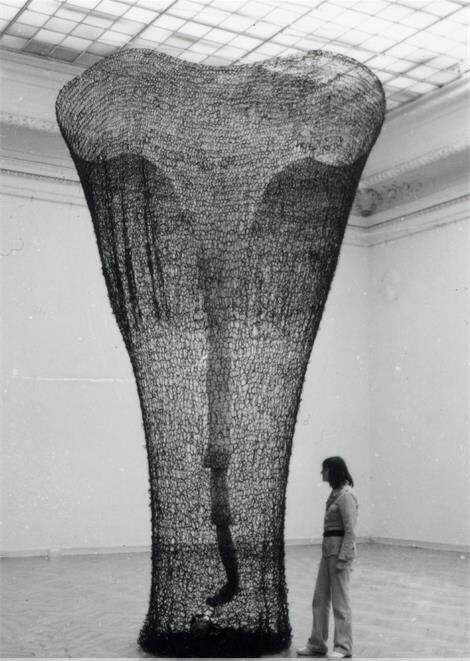

The 1960s and 1970s were a period of great international success of Polish fibre artists and multiple individual exhibitions in Poland. Their highly innovative work was already noticed during the 1st International Tapestry Biennial in Lausanne in 1962, where tapestries by Magdalena Abakanowicz, Ada Kierzkowska, Jolanta Owidzka, Wojciech Sadley, Ada Kierzkowska , Maria ?aszkiewicz, Zofia Butrymowicz and Krystyna Wojtyna-Drouet stood out from the other works, most of which were elegant, decorative pieces. Unlike them, the Polish works utilised innovative materials such as sisal, handspun yarn, fleece, raw silk or thick cotton rope. They were usually created directly in the studio, bypassing the stage of design, in which they differed fundamentally from the French school of tapestries woven according to painted cartoons. The Polish artworks shared a sculptural and painterly approach to the material, a fondness for expressive textures, the use of multiple techniques and diverse weave structures, and above all, a spirit of constant experimentation in pursuit of new forms of expression. The distinct style was dubbed the ‘Polish school of textile art’ by the critics, a term that encompassed the abovementioned as well as many other artists of the period. Later, the spirit of innovation and experimentation was demonstrated by artists such as Barbara Levittoux-?widerska, author of full-scale web-like structures, or Urszula Plewka- Schmidt and Stefan Pop?awski, who combine textile art with photography.

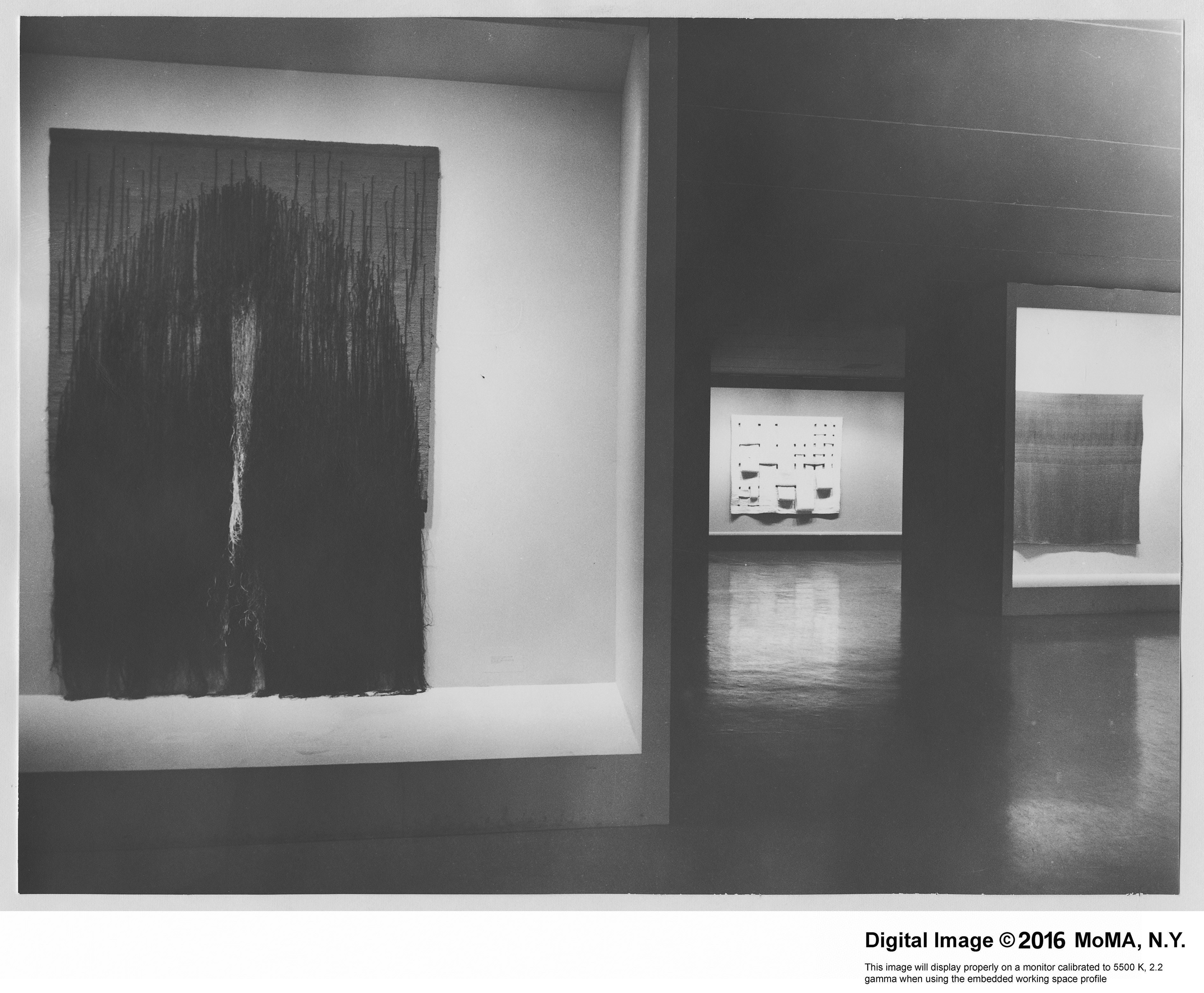

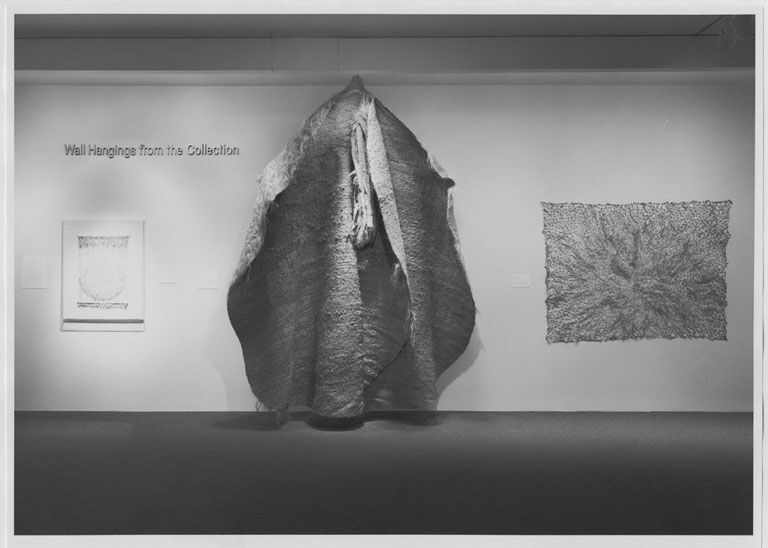

An important international watershed for textiles, already established as an art medium, came with the legendary Wall Hangings exhibition organised by Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969. Participating artists included a number of Poles such as Magdalena Abakanowicz, Zofia Butrymowicz, Barbara Falkowska, Ewa Jaroszyńska, Jolanta Owidzka, and Wojciech Sadley.

In 1960 was established the ?ód? Museum of the History of Textiles, renamed in 1975 to the Central Museum of Textiles. Its first long-time Director was Krystyna Kondratiukowa, responsible on behalf of Poland for the participation of artists in the Lausanne International Tapestry Biennials. Fully devoted to fibre art, the Director headed efforts aiming to establish collections of historical and contemporary textiles, promoted young weaver artists and supported their careers in art. Kondratiukowa was the initiator and organiser of regular presentations of textiles in ?ód?, first held in 1972 as the National Triennial of Industrial and Unique Textiles, and from 1975 in a new format as the International Triennial of Tapestry.

In the 1970, the Lodz Academy of Art became an important centre of fibre art. Following demands of the national authorities, the Academy had narrowed down its field to a single specialisation related to the textile industry centralised in ?ód?. Established before WWII, the State Higher School of Visual Arts, renamed in 1996 to the W?adys?aw Strzemiński Academy of Fine Arts, continues to this day the rich tradition of unique textiles and defines new directions for the art discipline it has followed since its inception. The most famous pedagogues from the Academy in ?ód? participating in the Tapestry Biennial in Lausanne were Professor Janina Tworek-Pierzgalska and Professor Antoni Starczewski. Their disciples and followers of the tradition were and are the artists of the younger generation today, also professors responsible for education of the successive generations of art students active creators on the Polish and international art scene. They are: Professor Jolanta Rudzka-Habisiak, Professor Ewa Latkowska- ychska and Professor W?odzimierz Cygan, all of them still experimenting, for whom teaching work as a duty of art is equally important as their individual artistic practice.

Professor Irena Huml’s book Contemporary Polish Textiles is the most complete account of the phenomenon of the Polish school of fibre art and a record of the politically perilous and artistically prolific historical era. The extensively illustrated publication summarises many years of Huml’s work as the Polish authority in fibre art, researcher, art critic, exhibition organiser. The book came out in May 1989, at the time of strong political tensions in Poland preceding the Parliamentary election which led to the appointment of the first sovereign government after WWII.